Sponsored by:

Designing a Sustainable and Affordable Cooling Technology for Mattress

Cameron King, Dio Oey, Lakshmi Prerana Panchumarti, Elijah Tan., Thomas Thwaite, Wendi (Allen) Wu

Heat Flux

Testing description

Heat flux [W/m^2] is defined as the rate of heat transfer per unit area to/from a surface. While sleeping, users give off body heat, which can become trapped in the space between the blankets and the mattress. Depending on the thermal conductivity and thickness of the uppermost mattress layers (as well as the temperature difference between both sides), a certain amount of heat will be transferred through, while the remaining heat stays and contributes to a feeling of excessive warmth. The greater the heat flux, the less heat remaining near the user, and thus the lower the chance of the sleeper overheating during the night.

In our study, heat flux represents a screening method for evaluating different mattress materials and potential prototype designs. Serta Simmons typically performs heat flux experiments on smaller scale samples (non-full mattresses) over a period of 1 hour. To mimic a human body, a hot plate is applied to the component and maintains a temperature in the range of 37-39 °C. The ambient temperature of the testing room was kept at 19 °C.

System entitled “SiliconeNet_L_L_C”. The picture shows the stacking order, with the net on top. The net tested was made by cutting triangular holes out of a flat sheet of silicone.

System entitled “L_SiliconeMatrix_C”. The picture shows the stacking order, with latex on top. The sample matrix used in all heat flux tests had a vertical thickness of 0.5 inches, with an average cell size of 20.25 cm2 and 2.8 mm thick silicone bars.

The basic test setup for all heat flux tests. The hot plate was set to a temperature of 37-39 °C and flipped onto the uppermost component. The upper sensor (Sensor 1), placed between the hot plate and uppermost material, is the source of the data reported in this document.

Result

1

2

3

1

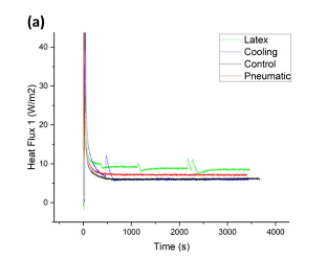

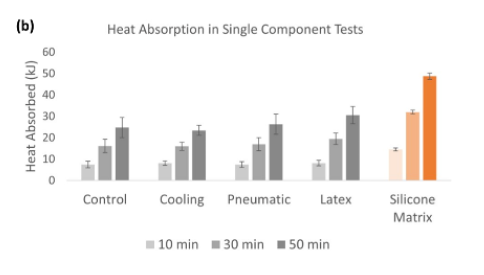

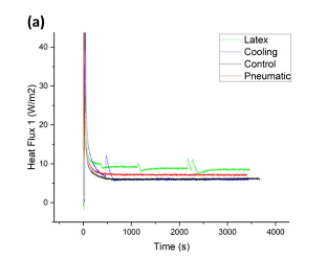

An individual trial of heat flux data is shown in Figure 1. In order to make quantitative comparisons between the samples, heat flux data is integrated and reported as the cumulative heat absorbed by the sample at three different time intervals (10 min, 30 min, and 50 min). Figure 2 shows the average heat absorption of the standard foam samples, as well as initial data for the prototype alone. Among the foam samples, latex showed the highest heat flux and heat absorption (Figures 1 & 2), which matches our expectations from preliminary research. The data supports the idea that latex foam offers greater cooling over traditional foams. Additionally, the silicone matrix prototype (as an isolated component) demonstrated the best performance at all time intervals

The initial results prompted further heat flux testing, and this time the goal was to test systems of comparable thickness (approximately 2 inches). The configurations were as follows: 2 layers of control foam; 2 layers of latex + 1 control; latex + silicone matrix + control (Appendix B-2); flat silicone net + 2 layers of latex + 1 control

Figure 3 shows the average heat absorption for the systems described above. As in the case of the single component tests, the silicone matrix afforded higher heat flux than the simple foam counterpart. This is validated by the higher heat absorption values for the L_SiliconeMatrix_C system compared to the C_C and L_L_C systems. The best performing system was the SiliconeNet_L_L_C, which can likely be explained by the layer ordering we used. The silicone net was directly contacting the hot plate, whereas the silicone matrix was separated from the hot plate by a layer of latex foam. Silicone is much more thermally conductive than foam, so it makes sense that it pulled much more heat into the system. Though this setup for the net confounds the heat adsorption comparison slightly, we chose this because our revised proposal suggests the inclusion of the net in a quilted top layer. In this scenario, the net would be extremely close to the sleeper, so it made sense to collect data to this effect.

It is worth noting that the total heat absorption values are much closer between each of the systems, as opposed to the single component tests (Figure2), but the inclusion of silicone clearly results in improvement over the foams alone. The readings were also very consistent between trials, so the standard deviation of the data is low. Overall, these findings support the inclusion of a conductive material like silicone in the comfort layer to improve the thermal performance of the mattress. The matrix and net designs both performed well in heat flux because they provide a continuous layer for heat to travel through.